“Just don’t believe you’re going to tell me something I haven’t heard before,” warns Mr. Verge at the beginning of Lars Von Trier’s latest (and perhaps final) film, The House That Jack Built. His warning is for Jack, a serial killer answering for his crimes at the end of his life with Virgil in his own personal Inferno. We’re treated to commentary from both of them: Jack boasting about his life structured around sadistic violence, and Verge’s increasing impatience with his stories and philosophies. Undeterred, Jack regales us with five so-called randomly selected incidents that best represent his life.

Jack’s first kill isn’t even premeditated, to give an idea of how haphazard a murderer he is. Rather, it was egged on by a woman who even cynical Verge describes as “admittedly unbearable.” She cajoles Jack into giving her multiple rides to get her jack repaired by a mechanic to ultimately fix her car. It’s hard to determine where her nosy personality ends and where Jack’s misogyny begins as he recalls their encounter. In any case, her inappropriate behavior puts her in an exciting position in relation to violence: a white woman in damsel in distress mode, sneering and highlighting every opportunity Jack has to kill her and every mistake he makes in the process. When comparing his demeanor and van to that of a serial killer doesn’t sufficiently irritate him, she retracts her assumptions. “You don’t have the disposition for that sort of thing. You’re way too much of a wimp to murder anyone.”

Uma Thurman plays the victim in question, who strikes me as a comical representation of white women’s self-directed true crime bloodlust. Though the term true crime is a more recent incarnation, the phenomenon of trashy entertainment made up of dramatized real-life murders is not new, evolving from radio shows to daytime television to podcasts. Victim #1 essentially brats Jack into breaking her face open with her jack, a truly nauseating pun that betrays the pitch-black comedy yet to come. While she initially pegs him as a serial killer as a neg, Jack interprets the situation as a sign of his calling.

Though Jack performatively owns the psychopath title in an attempt to impress and/or offend Mr. Verge, the first tale Jack tells him implies that he’s not fully culpable, that she was simply asking for it. He proceeds to elaborate on his antisocial urges from childhood, taking pleasure in watching gardeners toil away at tall grass and lethally mutilating a duckling. Still, his shirk of agency in this first incident is notable. Jack isn’t a standard depiction of a sociopathic murderer so much as an effigy of serial killer iconography as the archetype stands in true crime; he might not be the Ripper, but Jack is a ripper for sure. Matt Dillon brings a strong Ted Bundy aura to the role, though not our new sexy Efron-Bundy, but an uncharismatic, hulking oaf. As any true crime devotee worth their salt will tell you, Bundy’s image as a ladies’ man-cum-ladykiller was a narrative pushed by the press to generate intrigue. And much like Ted, Jack buys into his own hype and uses the potential thrill of being caught as a motivator.

Rather than succeeding because of any finesse or natural talent, the world is built for men like Jack to stumble their way into safety by the grace of circumstances outside of their control, such as the buffoonery of police officers or the weather disappearing evidence. Think Patrick Bateman in American Psycho (2000) dragging a body through a lobby in a Jean Paul Gaultier overnight bag. Jack views these coincidences as signs of giftedness, evoking Glenn Gould and Picasso not minutes after his first sloppy murder. By his second (punctuated by several follow-up visits to the crime scene to soothe his obsessive cleaning compulsions), he’s established a moniker for himself: Mr. Sophistication.

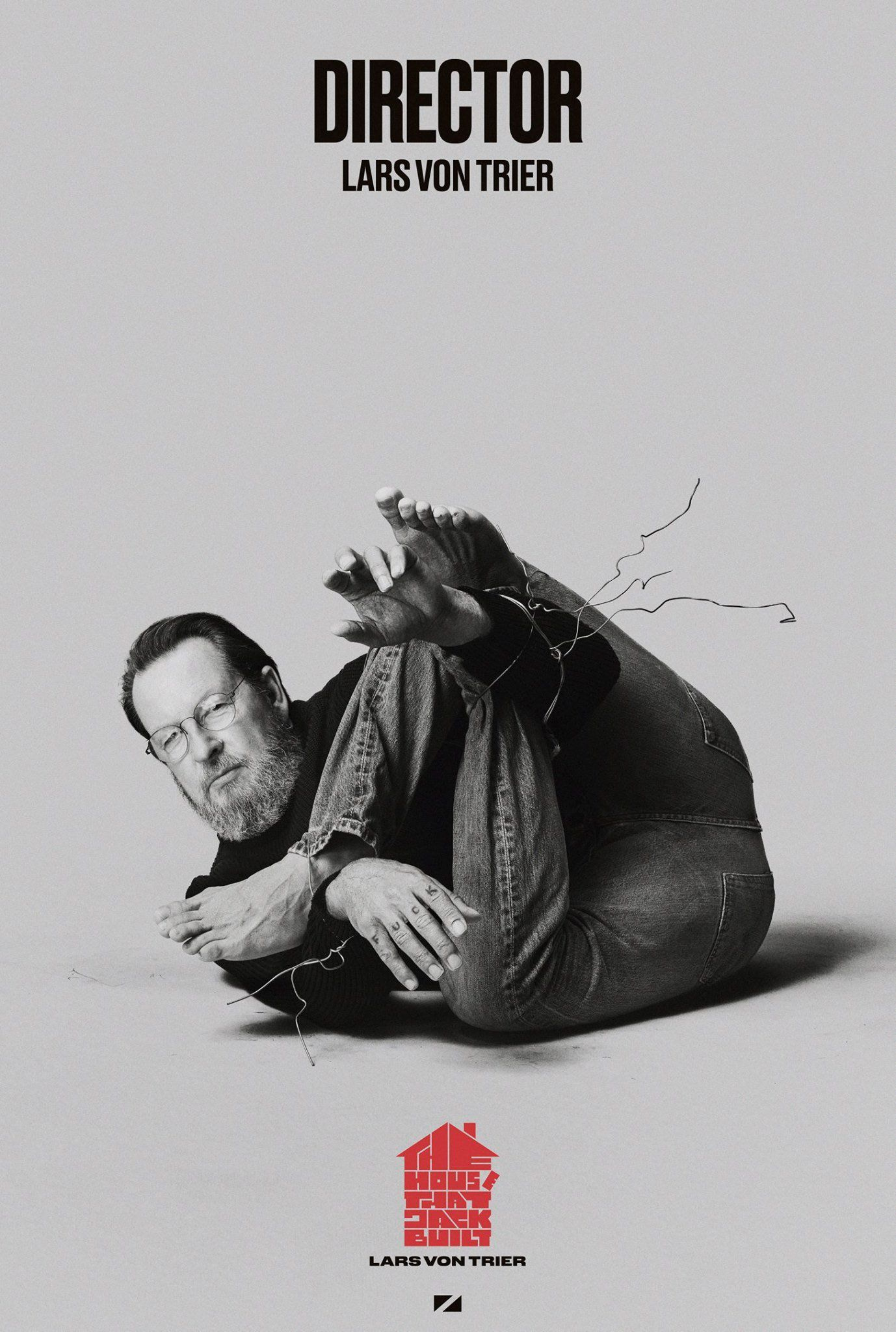

“A fucking neurotic riddled with obsessive compulsions and a pathetic dream of something greater,” Verge snarls early in the film, bringing to mind Lars’ personal struggle with OCD. The man has a dual reputation as a volatile enfant terrible hellbent on making every asshole in the audience of the Cannes film festival clench, and a trembling neurotic with a debilitating fear of flying. Now, this might be hard to believe, but the guy who has FUCK YOU knuckle tattoos might be a little sensitive about what other people think. And indeed, the more we hear Verge criticize Jack’s artistic vision, the more apparent the device of Jack as Von Trier’s self-insert becomes.

Lars is far from the first director to make a film about the pained process of wrangling with violence as a filmmaker, but he’s one of the more annoying directors to do it. I love a large portion of the guy’s work, but that’s undeniable. Over the years, you can track his public image through the Cannes Film Festival: from flipping off the judges for not awarding Europa the Palme d’Or in 1991 to demolishing Kirsten Dunst’s chance at an Oscar in mere minutes by empathizing with Hitler twenty years later at the press conference for Melancholia. Combined with his infamous clashes with Björk on the set of Dancer in the Dark, where he verbally abused her and dismissed one of his co-worker’s sexual harassment of the pop star, this exposition isn’t a good look for his singularly bleak visions.

“Why are they always so stupid?” Mr. Verge asks after hearing about the fourth incident, wherein Jack berates and objectifies his supposed girlfriend, Jacquelyn, before slaughtering her in a way particularly relevant to his depraved misogyny. “All the women you kill strike me as seriously unintelligent.” Verge is echoing various critiques of Lars Von Trier’s portrayal of women by pressing Jack on this. Whether this is meant as an apology or yet another “fuck you” is unclear. Still, it certainly stands as an acknowledgment of the tension between feminist and anti-feminist interpretations of female suffering in his work. Is a character like Bess from Breaking the Waves (1996) a loveless portrayal of a mentally and emotionally stunted woman, or does the film empathize and ache with her unfair treatment?

Accusations of cruelty distinct from his interpersonal treatment of cast and crew have been leveled against his movies for much of his career as well, echoing Mr. Verge’s dismissals of Jack’s excuses and explanations for his crimes. Jack displaces the more theoretical parts of his work unto Mr. Sophistication, a persona named after nightclub owner Cosmo Vitelli’s right-hand man in John Cassavetes’ messy masterwork The Killing of a Chinese Bookie (1976). Whereas Jack is merely driven by primal urges, at one point comparing himself to an ermine in a hen house to explain why he just had to run over an elderly woman, Mr. Sophistication takes artistic inspiration from a bastardized idea of a higher power. He drags Virgil through basic architecture and history to explain the artful merit of human suffering, bringing the viewer along for the process, creating a parody of a Lars Von Trier film viewing experience. The Bookie reference isn’t spelled out in the film, maybe out of Von Trier’s own shyness concerning paying respect to his elders (compared to how freely he namedrops authors and books he doesn’t seem actually to understand), but Cassavetes’ shadow has stood over his work dating back to the Dogme 95 Manifesto.

Claus Christensen writes that “the technology has to adapt itself to the acting, not the other way round, and the director has to seize the small miracles of the moment,” a philosophy directly stemming from Cassavetes’ pioneering methodology of decentering traditional plot in favor of personality, both of the characters and the actors themselves. Perhaps that’s easier done when you’re friends with forces of nature like Gena Rowlands and Ben Gazzara who agree to act in your movies; nevertheless, the spirit has been present in much of the independent cinema of the latter part of the 20th century, including Dogme 95. Not only that, but Lars’ attempts to get Tarkovsky’s posthumous approval after he shat on The Element of Crime (1984) actually pay off here, the end of Virgil’s journey with Jack departing harshly in tone from the gritty thriller preceding it and veering into a more atmospheric territory.

Written in collaboration with fellow Danish director Thomas Vinterberg, the “Vow of Chastity” swears off elements of mainstream filmmaking such as post-production effects, non-diegetic music, superficial violence, and more. Lars only made one certified Dogme 95 film himself, though the impact of its ideology is undeniable in his later work. The near-cartoonish levels of violence found in movies like Antichrist (2009) and Nymphomaniac (2013) read like a contrarian take on the Dogme approach to violence, depicting sexual misery with the unflinching lens of the Dogme touch even without beginning to approach the asceticism in that movement. It’s also important to bear in mind that not a single one of the official 35 Dogme films follows every single one of the rules: an intentional nod to the imperfect nature of life and therefore film, and an excuse for Lars to be a troublemaking little shit as per usual.

Watching Jack attempt to shoot multiple people at once by lining them up together tied down is evocative of a frustrated director throwing a tantrum over achieving the elusive perfect shot, something Cassavetes actively dismissed. “Audiences go to the cinema to see people: they only empathize with people and not with technical virtuosity” (Cassavetes on Cassavetes, 74). Obviously, the approach is very different, but the desire to expose the ego and artifice that comes with better-funded, mainstream cinema is present both in the Dogme 95 films and Lars’ subsequent stark ventures into thrillers and horror. Unlike Cassavetes, though, Lars is happy to indulge in genre filmmaking so long as Lars can fully explore his edgy sensibilities.

As critical as the film is of Jack, he’s explicitly an extension of Lars as a director, and he obsesses over his shot surrounded by the ever-increasing collection of bodies. Though The House That Jack Built is quite literally built upon a foundation of superficial violence, the camerawork still manages to center the actors’ performances and interactions with one another with its dynamic zooms, the editing emphasizing moments of kinetic importance. The kills strike a balance between haunting realism and stylized sadism, Lars’ writing becoming one with Jack’s house of work. If this is the note that the director chooses to go out on, it’s an impressive culmination of his influences, insecurities, and flexes.